“An Introduction to the Strong Mysteries of Egypt’s Lineage Pharaohs”

In ancient Egypt, women rulers kept the society stable in times of potential turmoil. Can we use those lessons today?

While our Queens have been legendary, Theresa May is only the second female to have held the title of British Prime Minister – and a woman has yet to be elected to the highest office in the United States. But 3,000 years ago in ancient Egypt it wasn’t unusual for women to rule—and some became all powerful, like Cleopatra and Nefertiti. Yet as Kara Cooney explains in her new book, When Women Ruled the World: Six Queens of Egypt, those women were ultimately only placeholders for the next male to take the pharaoh’s throne.

When National Geographic caught up with Cooney by phone in Los Angeles, she explained why Hatshepsut was so perfect; how Cleopatra grew up in a family that makes the Sopranos seem like lambs; and what these women symbolise for their society—and ours.

Let’s start with one of the last, but most famous, Egyptian queens: Cleopatra. You say, “She combined brilliant leadership with a productive womb.” Tell us about the Ptolemaic dynasty, and how Cleopatra used those two qualities to rule.

That’s a giant question so, as the academics say, let me unpack it. Growing up as a Ptolemy must have been a PTSD-inducing experience. Every Ptolemy son or daughter had their own entourage, their treasuries, their own sources of power and also shared power, but within a very exclusive system of siblings.

And killed each other with impunity and regularity. My favourite Ptolemaic story is Cleopatra II, who was married to her brother. They got in a massive argument and the brother was killed. Then she married another brother. Her daughter, Cleopatra III, then ended up overthrowing her mother and taking up with her uncle, Cleopatra II’s brother, kicking the mother out into exile. The uncle then sent her (Cleopatra II) a package containing her own son, cut up into little bits, as a birthday present. Then they all get back together for political reasons.

Cleopatra is probably the only woman in our story who uses her reproductive abilities like a man, to create a legacy. The other women are either ruling on behalf of a younger child or they’re ruling because there is no male offspring and are stepping in during years when they couldn’t produce any children. Cleopatra used her productive womb to have children with two Roman warlords. She had one child with Julius Caesar, three children with Mark Antony—twins, no less—and she survived it. She then carefully placed each child in charge of a different part of her growing Eastern Empire, in competition with the Western Roman Empire. If it weren’t for the boneheaded decisions made by Antony, the Roman warlord she was partnered with, we would maybe talk about her and her legacy differently.

She has come down to us as a great beauty, but we have to assume that she was partially a product of incest. And incest did not make people beautiful. I am thinking of Charles II’s giant head, how he needed special pillows and couldn’t chew. Cleopatra’s coinage doesn’t show her as a great beauty. What is written about her talks, rather, of her wit, conversation, and intelligence. Whatever it was that drew these Roman warlords to her, she used it. She used personal connections better than any of the other women in our story.

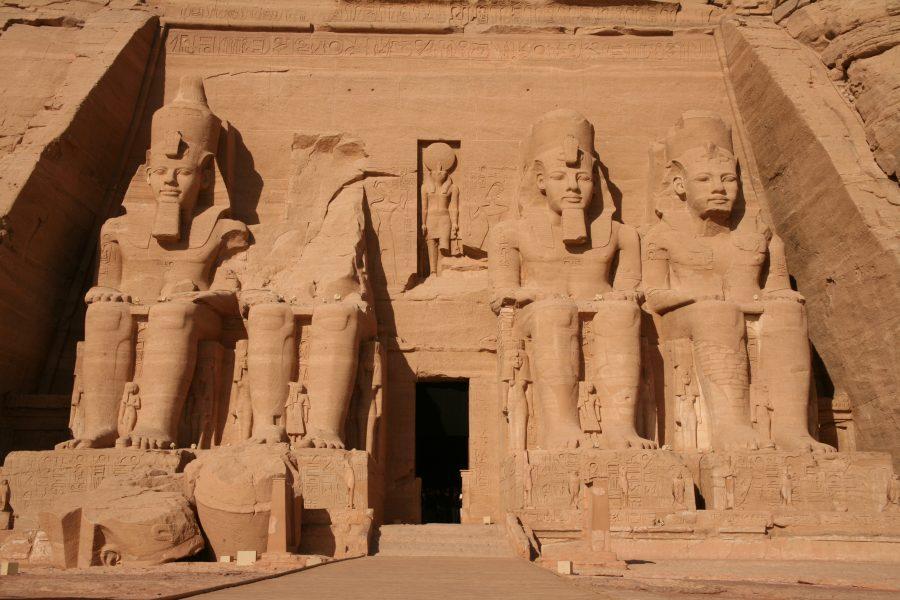

Nefertiti is the trickiest of our women to talk about because she is only just now being discovered by Egyptologists for what she was. That is, a leader of her people. We have thus far only discussed her as a beauty, as evidenced by the bust in Berlin’s Neues Museum. But when she became a political leader she changed her identity. She had herself renamed and was no longer depicted in that feminine way.

When I say that Nefertiti was the most successful of our feminine leaders what I mean is that she cleaned up the mess that the men before her had made. She used her feminine emotionality to do so. She wasn’t interested in her own ambition. She didn’t even claim it in a way historians can talk about her as having been in power. She hid all the evidence of herself having taken power.

Egyptologists still fiercely debate whether she became co-king at all, and certainly whether she became sole king. If she did, she had to erase her feminine identity of beauty and allure. That, right there, speaks volumes about what political power is—and what it does to a woman.