In Egypt, archaeologists have discovered over ten crocodile mummies that date back 2,500 years.

The remains include five reptile heads and five nearly intact specimens.

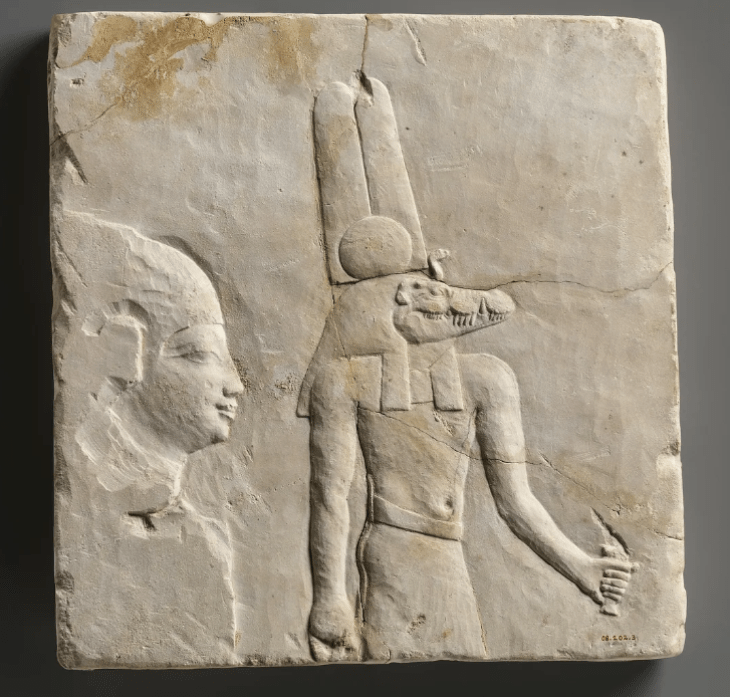

When archaeologists excavating an intact tomb at Qubbat al-Hawā, a necropolis on the western bank of the Nile River, discovered a cache of mummified crocodiles in 2019, they were not entirely surprised. After all, such finds are common in Egypt, where ancient humans preserved dead animals as sacred offerings, food for the afterlife, or incarnations of specific deities. Crocodiles, for example, were associated with Sobek, creator of the Nile and powerful god of fertility.

Upon closer examination, the team realized that the reptiles were preserved differently from most mummified crocodiles. As the authors write in the journal PLOS One, the ten crocodiles were mummified without resin or evisceration of the remains, two typical components of the process. According to the study, the animals, composed of five heads and five “more or less complete bodies,” presented different levels of conservation.

“Most of the time I’m dealing with fragments, with broken things,” lead author Bea De Cupere, an archaeozoologist at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, tells Sam Jones of the New York Times. “Hearing that you have ten crocodiles in a grave is special.”

The reptiles measure between 6 and 11.5 feet long. They appear to represent two different species: the Nile crocodile and the West African crocodile. As De Cupere explains in a statement, the animals may have been buried in sand pits elsewhere to undergo natural mummification before being exhumed and moved to Qubbat al-Hawā around the 5th century BC.

Because the mummies contain no resin or linen (insects ate almost all of the bandages used to wrap the remains long ago), researchers were able to study them in situ, without using special technology such as X-rays and CT scans.

“The absence of linen and resin bandages allowed us to directly carry out a detailed study of the tissues and bones preserved in all individuals,” De Cupere tells Newsweek’s Aristos Georgiou. “…In the case of the five isolated skulls, the heads were extracted when the crocodiles were already [dry].”

Identifying the cause of death of a mummified crocodile is easier for some specimens than others. In 2019, a separate group of archaeologists used synchrotron scanning to analyze the remains of a roughly 2,000-year-old mummy housed at the Museum of Confluences in Lyon, France. The animal suffered a skull fracture whose size, direction and shape indicated that “it was made in a single blow, presumably with a… thick wooden club, aimed at the rear right side of the crocodile, probably when it was resting on the ground,” according to the researchers wrote in the Journal of Archaeological Science. The findings suggested that ancient Egyptians acquired crocodiles for mummification through hunting, in addition to previously known procurement methods, such as recovering corpses or raising animals for the sole purpose of slaughter.

Interestingly, none of the Qubbat al-Hawā crocodiles suffered injuries associated with a violent death. Instead, the authors note, the reptiles may have died from drowning, suffocation or prolonged exposure to the sun. Traces of rope discovered on several of the mummies may indicate that they were “bound, probably until death from dehydration,” co-author Alejandro Jiménez-Serrano, an Egyptologist at the University of Jaén in Spain, tells Insider’s Marianne Guenot.

From cats to birds to snakes, animal mummies “are probably the most numerous object to come from ancient Egypt,” Laurel Graeber told the Times in 2017, Yekaterina Barbash, co-curator of a previous exhibition on the subject at the Brooklyn Museum. Although the exact purpose of the mummies remains a mystery, the exhibition argued that they sometimes served as requests for help to the gods.

“We believe that if you had a particular request,” co-curator Edward Bleiberg explained to the Times, “you would arrange with the priests to have them make an animal mummy of the appropriate type to bring you closer to the god you wish to approach.”

The ancient Egyptians asked Sobek, who was usually depicted with the head of a crocodile, for fertile land and protection from deadly reptiles.

“The crocodile was seen as a very powerful animal,” said Rita Lucarelli, an Egyptologist at the University of California, Berkeley, in a 2021 episode of the “Fiat Vox” podcast. “It could live on land and in water. It could attack very quickly. It was very powerful and also unpredictable. He had a lot of physical strength. … In the wild, [crocodiles’] diet consists mainly of fish, but they are actually ready to attack anything that happens.”

While De Cupere and his colleagues have tentatively dated the crocodiles and identified the species represented, they hope to confirm these findings in the near future using radiocarbon and DNA testing.

Overall, Jiménez-Serrano tells the Times: “The discovery of these mummies offers us new insights into ancient Egyptian religion and the treatment of these animals as offerings.”