An Antique Tibetan Bowl Displays Alexander the Great—the Jewish Interpretation

silver bowl with Greek-style reliefs found in Tibet decades ago does not show scenes from Homer’s “Iliad,” as has been postulated. Rather, the bowl shows Alexander the Great and his servants, based on a Jewish version of the “Alexander Romance” dating to the fifth or sixth century C.E. that had been previously unknown, according to a new paper published in the Bulletin of the Asia Institute.

Alexander himself is shown three times on this bowl: once picking fruit from the Tree of Life, and twice drinking from the Fountain of Life, claim authors Anca Dan of CNRS, University Paris Sciences & Letters, and Frantz Grenet of the College de France.

The bowl also has the earliest known depiction in the Far East of the terrestrial Paradise, the two scholars say in their paper. Their innovative view of the bowl’s Jewish origin is based, among other things, on the fact that the nude figure they believe represents Alexander the Great, shown drinking the Water of Life and picking the frankincense from the Tree of Life – is circumcised, which was not a habit known among the Macedonians.

If Dan and Grenet are right about their interpretation of the dish’s Jewish origin, then the bowl indicates that Jews involved in long-distance trade along the Silk Road played a role in the evolution of the Alexander legends in the centuries following the king’s death. In short, this one wee bowl indicates Jewish influence in medieval Central Asia (between northern India, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Uzbekistan) centuries before the Arabic conquest.

Medieval Fanfic

The earliest versions of the Alexander Romance – accounts of real and imagined exploits of the powerful ruler of ancient Macedonia – which were written in Greek, Latin, Armenian and Syriac, date to the third century C.E. and relate to the boy king’s military campaign that began in his homeland and reached as far as India. The main text of the Romance was wrongly ascribed to Callisthenes, Aristotle’s nephew and Alexander’s official historian. Two extant texts describe the Jewish legend that Alexander the Great arrived at the Garden of Eden. The first is a passage in Aramaic in the Babylonian Talmud, written sometime in the sixth century C.E. It relates that Alexander washed his face in the Water of Life and arrived at the Gate of the Lord, through which only the righteous may enter, based on Psalm 118:20: “He ascended along the length of the entire spring until he reached the entrance of the Garden of Eden. He raised a loud voice, calling out: ‘Open the gate for me!’” (Tamid 32b, Babylonian Talmud).

The second, Sefer Toldot Alexandros ha-Makdoni (the history of Alexander the Macedonian), is part of a collection of Hebrew texts compiled by Eleazar of Worms (now in Germany) in roughly 1325, which is preserved in a manuscript in Oxford. It describes how Alexander was circumcised by his doctors so that he could enter the Garden of Eden as a righteous person. The images on the bowl seem to combine elements from both the Tamid and the Sefer Toldot Alexandros ha-Makdoni. If so, they indicate that the Jews of Central Asia had developed their version of Alexander’s accession to Paradise before the Islamic conquest, Dan and Grenet contend.

In The Garden Of Eden

The interior of the bowl is smooth, as befits practical tableware. The exterior bears a dense riot of imagery done in reliefs that project up to 9 millimetres above the silver surface, the authors explain. It shows six male figures. According to Dan and Grenet, Alexander himself is shown three times, once picking fruit from the Tree of Life, and twice drinking from the Fountain of Life. The researchers recognize two Indian carriers of the Water of Life, and a priest playing on an Indian drum with strings (dhol).

Between each man is a gnarled tree with a snake climbing up toward a nest. In each nest the birds are at a different stage of life: In one there are eggs, in another, a bird is feeding chicks, and finally, one nest shown empty could indicate that the serpent ate them. Between the two figures of Alexander picking fruit from the Tree of Life and drinking from the Fountain of Life, however, the birds are nesting in flourishing trees, as in an eternal spring, the authors explain. As for the Jewish bent of the Alexander depiction, the state of his penis is unmistakable even though the bowl is very small: 6.5 centimetres in height, 21 centimetres in rim diameter and with a capacity of 120 cubic centimetres, which is about half a cup. Its weight corresponds to 250 drachms, in keeping with standard measurements used in ancient Bactria and Sogdiana (4.43 to 4.55 grams).

Clearly, the absence of the monarch’s foreskin was of importance, which argues that the artisan or maybe the commissioner of the art was Jewish. The ancient Greeks did depict naked young men, frequently, but did not circumcise. Neither did Macedonians, or the Indians or Iranians conquered by the Macedonians, Dan observes.

Speaking of prohibitions, Jews aren’t supposed to show graven images and nudity isn’t a hallmark of Jewish art. The bowl may have been commissioned by a Hellenized Jew living in central Asia who adored Alexander but did not necessarily shrink at such depictions, the researcher suggests.

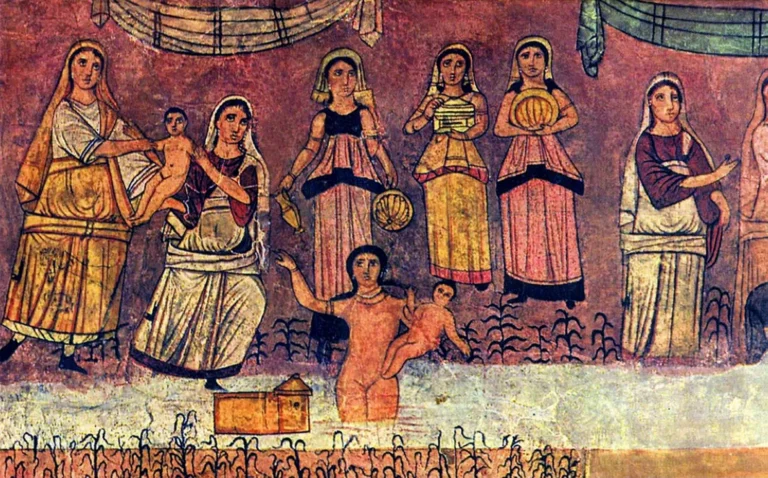

There are precedents of nudity in ancient Jewish art: for example, the synagogue of Dura Europos, a city that existed in Syria from 300 B.C.E. to the year 256 C.E., has frescoes showing people dressed to the nines but also a nude woman in the water – a maid or Pharaoh’s daughter herself – rescuing baby Moses.

Back to the bowl. Even if it was commissioned by a Jew, why would the conqueror have been shown thus trimmed? Because, according to the Jewish version of his “Romance” (from which only medieval versions survive), he had to be in order to visit the Garden of Eden, albeit briefly. The bowl, actually made of a silver alloy with a high concentration of copper, had been obtained in Lhasa half a century ago by Dr David Snellgrove, a professor of Tibetan Buddhist studies at the SOAS University of London, the authors say. The reinterpretation of it by Dan and Grenet was undertaken based on photographs of the bowl, which today belongs to a private owner in Japan who displays it in the Ancient Orient Museum in Tokyo.