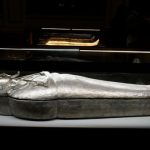

Emperor Maximilian I gifted King Henry VIII with the Horned Helmet (1512–1514 CE).

The Armet, colloquially known as “The Horned Helmet,” stands as a symbol of the intricate craftsmanship and diplomatic exchanges of the Renaissance era. Crafted between 1512 and 1514 CE by the renowned armorer Konrad Seusenhofer of Innsbruck, Austria, this helmet holds a storied history as part of a grand gift from Emperor Maximilian I to King Henry VIII of England.

During the early 16th century, armor-making flourished as both a necessity for warfare and an expression of artistic prowess. Konrad Seusenhofer was among the foremost artisans of his time, his workshop in Innsbruck being a hub of innovation and skill. It was here that the Armet, with its distinctive horned design, was meticulously forged.

In 1514 CE, Emperor Maximilian I, a key figure in the politics of Europe, sought to strengthen diplomatic ties with England. As a gesture of goodwill and alliance, he presented King Henry VIII with a lavish suit of armor, of which the Armet was an integral part. This gesture not only demonstrated Maximilian’s appreciation for Henry VIII but also showcased the craftsmanship of the Holy Roman Empire.

The Armet itself is a testament to both function and form. Its sleek design provided excellent protection to the wearer while allowing for ease of movement on the battlefield. The addition of the horn-like protrusions, while visually striking, also served a practical purpose, potentially deflecting blows away from the head in combat.

Beyond its utility, the Armet embodies the cultural exchange and diplomacy of its time. Made in Austria but gifted to England, it represents the interconnectedness of European nations during the Renaissance. It also reflects the prestige and power associated with armor, not just as a means of defense but as a symbol of status and nobility.

Today, the Armet resides in prestigious museum collections, revered as both a work of art and a historical artifact. Its journey from the workshops of Innsbruck to the royal courts of England speaks volumes about the social, political, and artistic landscape of 16th-century Europe. As we admire its craftsmanship and ponder its significance, we are reminded of the enduring legacy of those who crafted it and the leaders who wore it into battle.