Researchers Uncover Facial Reconstruction of Aɴᴄ̪ᴇ̴ᴛ Eɢŏᴘᴛɪᴀɴ Mᴜᴍᴍʏ Bᴇʟɪᴇᴠᴇᴅ ᴛᴏ ʙᴇ ᴛʜᴇ Wᴏʀʟᴅ’s Eᴀʀʟɪᴇsᴛ Kɴᴏᴡɴ Pʀᴇɢɴᴀɴᴛ Wᴏᴍᴀɴ. Beginning more than 2000 years ago

In a groundbreaking archaeological and scientific achievement, researchers have unveiled the facial reconstruction of an ancient Egyptian mummy believed to be the earliest pregnant woman ever discovered. This extraordinary find dates back approximately 2000 years, shedding new light on the lives and practices of ancient civilizations.

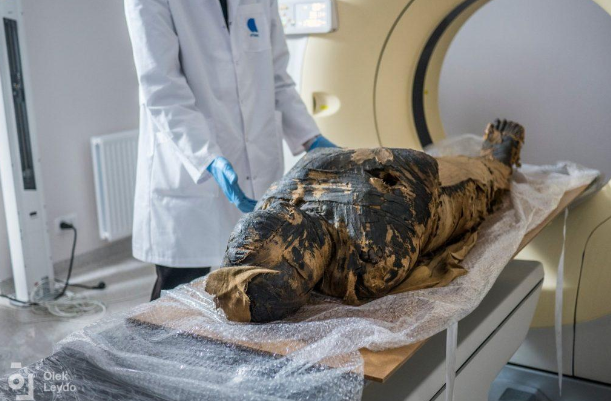

The mummy, discovered in the early 20th century, has been a subject of fascination and study for decades. However, it wasn’t until recently that advanced imaging technology and forensic techniques enabled scientists to delve deeper into her story. Initial scans and examinations revealed the presence of a fetus, making this mummy the first known case of a pregnant embalmed woman from ancient Egypt.

The facial reconstruction project was spearheaded by a team of international experts in fields ranging from archaeology and Egyptology to forensic science and digital imaging. Using a combination of CT scans, 3D modeling, and forensic facial reconstruction software, they meticulously rebuilt her facial features. This process involved analyzing the mummy’s skull structure, muscle attachment points, and other anatomical details to create a lifelike representation.

The final reconstruction presents a remarkably detailed and humanized visage of this ancient woman, providing a tangible connection to a person who lived two millennia ago. The team paid particular attention to cultural and historical accuracy, ensuring that the facial features were in line with what is known about the physical characteristics of ancient Egyptians from that period.

The discovery of the fetus within the mummy is particularly significant as it offers unique insights into ancient Egyptian burial practices and beliefs regarding pregnancy and the afterlife. Researchers suggest that the presence of the fetus indicates a possible cultural reverence for motherhood and fertility. It also raises intriguing questions about how ancient Egyptians dealt with the deaths of pregnant women and whether special rituals or embalming techniques were employed.

Dr. Zahi Hawass, a renowned Egyptologist involved in the project, expressed his excitement about the findings. “This mummy provides us with invaluable information about ancient Egyptian society, their medical knowledge, and their burial customs. The fact that she was pregnant opens a new chapter in our understanding of maternal health in antiquity.”

The team also explored the mummy’s health and lifestyle, using isotopic analysis to glean information about her diet and living conditions. Preliminary results suggest that she enjoyed a diet rich in proteins, indicative of a relatively high status in society. Additionally, wear and tear on her bones hinted at a life that, while privileged, was not devoid of physical labor.

The unveiling of the facial reconstruction has garnered worldwide attention, highlighting the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in archaeology. It underscores how modern technology can breathe new life into ancient remains, allowing us to connect with and learn from the past in unprecedented ways.

Future research on this mummy will likely focus on further understanding the circumstances of her life and death, as well as the broader implications of her pregnancy. The team hopes to publish a comprehensive study detailing their findings and methodologies, contributing valuable data to the fields of Egyptology and forensic science.

In conclusion, the facial reconstruction of this ancient Egyptian mummy, presumed to be the earliest pregnant woman ever discovered, marks a monumental achievement in archaeology and science. It not only brings us face-to-face with a long-lost individual but also deepens our understanding of the cultural and societal nuances of ancient Egypt. This remarkable endeavor exemplifies the power of modern technology to unlock the mysteries of the past, offering a poignant reminder of our shared human heritage.