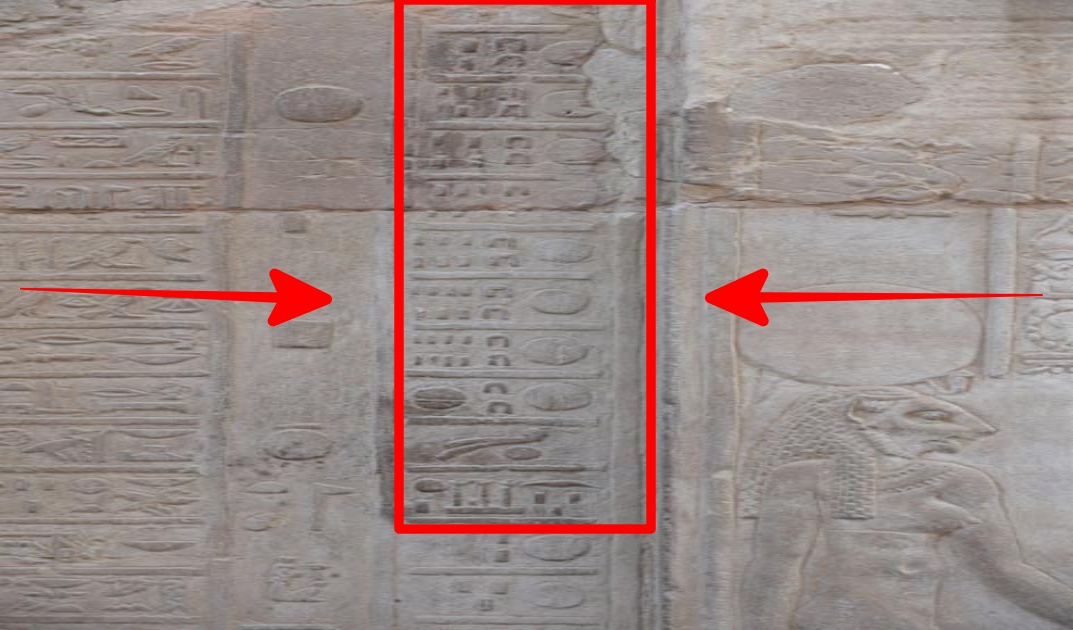

Change in the Hieroglyphic Calendar: Month XII to Month I at Kom Ombo Temple

The ancient Egyptians, renowned for their advanced knowledge of astronomy and mathematics, devised a sophisticated calendar system to track the passage of time and organize their religious festivals and agricultural activities. Among the many remnants of this calendrical tradition, the hieroglyphic calendar at the Kom Ombo Temple stands as a remarkable testament to the ingenuity and precision of ancient Egyptian timekeeping. In particular, the transition from Month XII to Month I, as depicted in the hieroglyphic inscriptions at the temple, offers valuable insights into the cultural, religious, and agricultural significance of the Egyptian calendar.

The Kom Ombo Temple, situated on the east bank of the Nile River in Upper Egypt, is dedicated to the worship of two ancient Egyptian deities, Sobek the crocodile god and Horus the falcon-headed god. Built during the Ptolemaic period (circa 180–47 BCE), the temple boasts a wealth of architectural and artistic treasures, including intricate hieroglyphic inscriptions that adorn its walls. Among these inscriptions is a hieroglyphic calendar that delineates the annual cycle of festivals and religious observances, as well as the agricultural seasons dictated by the flooding of the Nile.

At the heart of the hieroglyphic calendar is the transition from Month XII to Month I, a pivotal moment in the Egyptian calendar year. Month XII, known as “Mesut Rekh” in ancient Egyptian, marked the end of the agricultural cycle and the beginning of the inundation season, during which the Nile River flooded its banks, replenishing the soil with nutrient-rich silt and ensuring a bountiful harvest in the coming year. Month I, known as “Thout,” signaled the start of the new agricultural year and the planting season, as well as the onset of a new cycle of religious festivals and ceremonies.

The transition from Month XII to Month I held profound religious and cultural significance for the ancient Egyptians. It was a time of renewal and regeneration, symbolizing the cyclical nature of life and the eternal cycle of death and rebirth. The flooding of the Nile, known as the “Inundation,” was viewed as a divine blessing from the gods, particularly Sobek, the god of fertility and the Nile, who was believed to control the annual floodwaters. The hieroglyphic inscriptions at the Kom Ombo Temple likely included prayers and invocations to Sobek and other deities, seeking their continued protection and benevolence during the inundation season.

Moreover, the transition from Month XII to Month I was associated with the festival of “Wag Festival,” a joyous celebration that marked the beginning of the inundation season and the arrival of the floodwaters. The festival, which lasted for several days, included feasting, music, dancing, and religious ceremonies dedicated to Sobek and other deities associated with the Nile. It was a time of communal gathering and thanksgiving, as well as an opportunity for the ancient Egyptians to reaffirm their connection to the natural world and express gratitude for the blessings of the annual inundation.

The hieroglyphic calendar at the Kom Ombo Temple would have served as a visual and symbolic representation of these cultural and religious traditions, reminding worshippers of the cyclical nature of time and the importance of divine intervention in the agricultural cycle. The transition from Month XII to Month I, depicted in the inscriptions, would have been a focal point of religious observance and ritual activity, as priests and devotees gathered to honor the gods and invoke their blessings for the coming year.

In conclusion, the transition from Month XII to Month I, as depicted in the hieroglyphic calendar at the Kom Ombo Temple, offers a fascinating glimpse into the cultural, religious, and agricultural practices of ancient Egypt. It underscores the intimate connection between the Egyptian calendar, the annual flooding of the Nile, and the religious beliefs and rituals associated with the cycle of life and death. As we study and interpret these ancient inscriptions, we gain a deeper appreciation for the enduring legacy of Egyptian civilization and its profound understanding of the natural world.