Over 100,000 Years Ago, Neanderthals Partaked in the First Human Aquatic Activities

The story of human evolution is a narrative of constant discovery and reevaluation, often challenging our preconceived notions about the capabilities and behaviors of our ancient ancestors. Recent archaeological findings have shed light on the aquatic prowess of Neanderthals, suggesting that they were among the first humans to engage in aquatic activities over 100,000 years ago.

For decades, the prevailing view of Neanderthals depicted them as primitive brutes, lacking the cognitive abilities and adaptability of modern humans. However, this stereotype has been increasingly challenged by a growing body of evidence indicating their sophisticated tool-making abilities, complex social structures, and even symbolic behavior. Now, the discovery of archaeological sites such as the Mediterranean island of Crete and the coastal regions of Spain and Italy has provided compelling evidence that Neanderthals were not only capable of swimming but actively participated in aquatic activities.

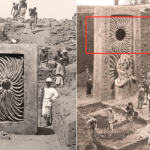

One of the most significant findings supporting this notion is the discovery of ancient stone tools on the island of Crete, dating back to approximately 130,000 years ago. These tools, including hand axes and scrapers, were found in association with fossilized remains of extinct animals and evidence of butchery, suggesting that Neanderthals inhabited the island and utilized its resources. The presence of such artifacts on an island necessitates some form of seafaring capability, implying that Neanderthals were able to navigate across bodies of water.

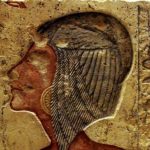

Furthermore, evidence from coastal sites in Spain and Italy has provided additional support for the aquatic capabilities of Neanderthals. Excavations at these sites have uncovered shells and other marine resources, indicating that Neanderthals not only exploited coastal environments for food but may have also engaged in fishing and shellfish gathering activities. This suggests a level of adaptation to coastal habitats and a willingness to venture into aquatic environments for sustenance.

The implications of these findings are profound and challenge our understanding of the behavioral flexibility and adaptability of Neanderthals. The ability to engage in aquatic activities would have provided Neanderthals with access to new food sources, expanded their territories, and facilitated cultural exchange with other populations inhabiting coastal regions. It also suggests a level of cognitive sophistication and innovation previously underestimated in Neanderthal populations.

However, the question remains: how did Neanderthals acquire these aquatic skills? While the exact mechanisms are still a subject of debate among researchers, several hypotheses have been proposed. Some suggest that Neanderthals may have learned these skills through observation and experimentation, while others propose that these behaviors could have been inherited from a common ancestor shared with modern humans. Regardless of the precise explanation, the evidence indicates that Neanderthals were far more adaptable and resourceful than previously thought.

In conclusion, the discovery of archaeological evidence indicating that Neanderthals engaged in aquatic activities over 100,000 years ago challenges traditional perceptions of their capabilities and behaviors. These findings underscore the need for continued research and reevaluation of our understanding of human evolution, highlighting the complexity and diversity of our ancient ancestors’ lifestyles. The story of Neanderthals as early practitioners of aquatic activities adds another fascinating chapter to the ongoing saga of human prehistory.