Desert of Death: Mass Skeleton Find in Sahara Uncovers Traces of Ancient Catastrophe

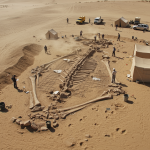

In a chilling discovery that evokes a scene from a dystopian nightmare, archaeologists have uncovered a vast graveyard of hundreds of human skeletons scattered across a desolate stretch of the Sahara Desert. Known as the “Desert of Death,” this barren expanse in Niger’s Ténéré region, often called a desert within a desert, revealed bones eerily aligned in rows, with skulls and spines stretching beyond the horizon, hinting at a forgotten catastrophe—be it a mass vanishing, genocide, or apocalyptic aftermath. Found during an expedition led by a team inspired by prior discoveries at Gobero, the site contains remains estimated to be 8,000–10,000 years old, accompanied by artifacts like ceramic pots, fishhooks, and ostrich eggshell beads, suggesting a once-thriving community. The organized arrangement of the skeletons raises haunting questions: was this a ritualistic burial, a massacre, or the result of a natural disaster? As global media and X users dissect the find, the world grapples with the mystery of what happened in this desert of the damned.

Preliminary analysis, drawing on techniques used in prior Sahara finds, reveals the skeletons belong to adults and children, with some showing signs of perimortem trauma—blunt-force injuries and possible projectile wounds—suggesting violence, though others appear undisturbed, indicating a possible mass burial event. Radiocarbon dating aligns the remains with the African Humid Period (14,500–5,000 years ago), when the Sahara was a lush savanna with lakes and rivers, home to hunter-gatherers and early pastoralists. Artifacts, including harpoon points and pollen traces of palm and fig trees, point to a sophisticated culture, possibly linked to the Kiffian or Tenerian peoples documented at Gobero. Skeptics argue the bones could be from a natural disaster, like a flash flood, or misidentified megafauna, but the deliberate alignment and trauma patterns challenge such claims. X posts speculate wildly, from biblical Nephilim to ancient warfare, while restricted site access due to the Ténéré’s harsh conditions—120°F temperatures and bandit risks—fuels conspiracy theories, despite calls for DNA analysis and 3D imaging to clarify origins.

The global reaction to this apocalyptic find has been intense, with images of the skeletal expanse flooding social media, drawing comparisons to mass graves like Jebel Sahaba or Nataruk, where evidence of prehistoric violence was found. Enthusiasts link the site to myths of lost civilizations or cataclysmic events, though claims of supernatural or extraterrestrial causes lack peer-reviewed support. Archaeologists, building on Paul Sereno’s Gobero discoveries, face challenges preserving the fragile remains against the Sahara’s relentless winds, with the site’s remoteness amplifying public intrigue and rumors of a cover-up, despite debunked narratives like those surrounding giant skeleton hoaxes. The eerie alignment suggests a purposeful act—ritual, massacre, or desperate survival—potentially tied to the Sahara’s desertification, which forced migrations and conflicts. As researchers probe this haunting tableau, the Desert of Death stands as a stark reminder of a lost world, urging humanity to uncover the truth behind a catastrophe that left hundreds entombed in sand, their story exposed by the merciless winds of time.