Gotland Burials Reveal Ancient Trends in Viking Body Modification

The examination of skeletal remains from cemeteries on Sweden’s Baltic Sea island of Gotland has revealed evidence of Viking body modification among the Norse people, shedding light on practices during the Viking Age (793 to 1066). These findings offer insights into the cultural and societal aspects of body modification among the ancient Norse population.

Fresh Discoveries Provide Insight into Viking Body Modification

This evidence under assessment included the skeletal remains males with horizontal grooves filed into their teeth, a curious practice that has been observed on Viking-era skeletons excavated elsewhere. But archaeologists have also found the remains of three Norse women who underwent a process that elongated their skulls to a noticeable degree. Significantly, these are the only three examples of this phenomenon ever found on Scandinavian territory, which makes this a rare and unique discovery indeed.

New information about the three women and the custom of skull elongation in Scandinavia was recently revealed in a study published in the journal Current Swedish Archaeology. The authors of this article and the research that inspired it were Matthias Toplak—a Swedish archaeologist with expertise in Viking burial customs—and Lukas Kerk—a doctoral candidate in archaeology at the University of Münster in Germany who is currently researching ancient traditions of body modification.

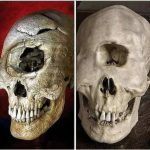

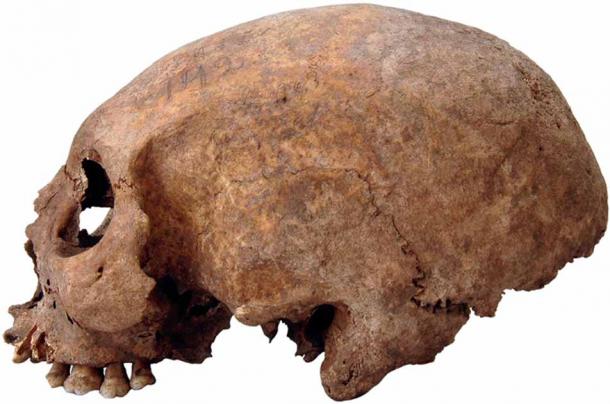

Artificially modified skull from the female individual in grave 192 from Havor, Hablingbo parish, Gotland. (Johnny Karlsson / Current Swedish Archaeology / CC BY 2.5 SE)

Unraveling the Mystery of Viking Body Modification

While skull elongation was almost unheard of in this particular time and place, it was relatively common practice in certain areas of southeastern Europe in the early medieval period. “In the regions where skull modifications were still a common practice in the tenth and eleventh centuries, this distinctive embodiment was presumably intended to increase the prestige, and possibly also the social status, of the individual,” the study authors wrote.

“It further defined the individual as a member of a certain social class or a specific ethnically, geographically or culturally defined group, even though indication of a higher social rank of individuals with skull modifications can only be found in isolated cases.”

The researchers believe these factors would have motivated the parents of the three Scandinavian women who were subjected to the elongation procedure, which can only be performed between the ages of six months and three years. But there is uncertainty here, since it seems the practice remained extremely rare on Viking territory.

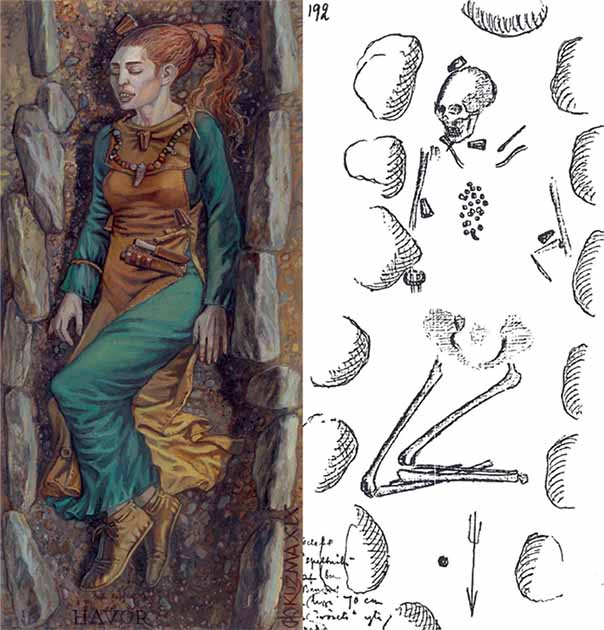

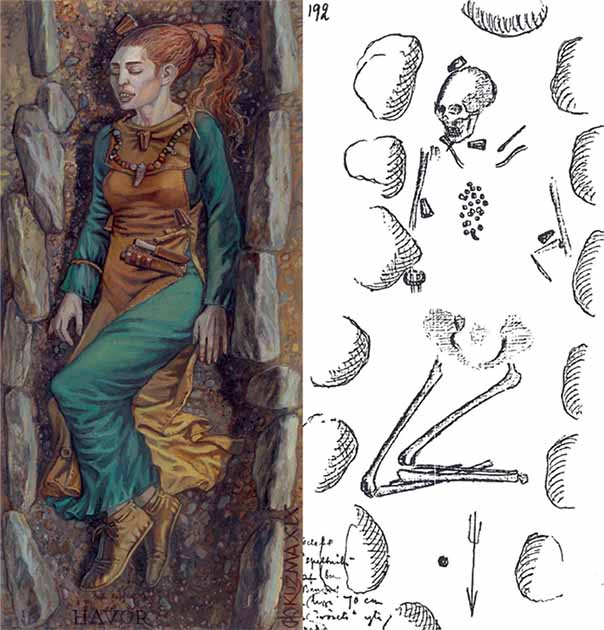

Drawing of grave 192 in Gotland of female with artificially modified skull (right) and artistic reconstruction of the burial (left). The burial sheds light on Viking body modification. (© ATA / Riksantikvarieämbetet, Excavations G. Gustafson 1884–1887; reworked by author (right); Mirosław Kuźma / Matthias Toplak 2019 (left) /Current Swedish Archaeology)

Skull Elongation in Viking Age Scandinavia

The three women with elongated skulls unearthed on Gotland were found in three different locations. Two of the three women passed away between the ages of 55 and 60, while the third expired at a much younger age (between 25 and 30). All three women live in the latter half of the 11th century, near the end of the Viking Age.

One of the older women was buried along with a plethora of fancy jewelry, including four distinctive animal-head brooches (a popular type of jewelry on Gotland during the Viking era). The other women’s graves didn’t feature such an abundance of valuable burial goods, suggesting that the older woman with the jewelry enjoyed higher social status when the three were alive.

Archaeologists know little about the physical mechanisms of skull elongation in western and northern Europe. They do know that elongation procedures in Central and South America in ancient times involved the binding of infants’ and toddlers’ heads with wood and cloth, which would remain in place long enough to alter patterns of skull growth. Presumably, something similar would have been done in Europe.

Toplak and Kerk believe that the practice of skull elongation was imported into Scandinavia from southeast Europe, possibly from Bulgaria, sometime between the 9th and 11th centuries. They are uncertain if the three women originally came from southeastern Europe and arrived on Gotland with their skulls already elongated, or if they were born on the island and underwent the elongation procedure there (or on the nearby mainland).

Whatever the correct scenario, it’s possible that their parents were merchants or traders from southeastern Europe who for one reason or another ended up living in Scandinavia after years of doing business there.

One thing that can be said is that the style of the three body modification procedures was the same. The fact that all three lived in the latter 11th century on the same small island suggests that they either knew each other or otherwise shared a common background.

Given the number of Viking Age cemetery excavations that have taken place, on Gotland as well as on mainland Scandinavia, the rarity of skull elongation stands out. “In late Viking Age Gotland, the social identity expressed by skull modifications probably lost its original significance,” Toplak and Kerk wrote in their Current Swedish Archaeology article.

“Regardless of whether the skull modifications were actually executed on Gotland, the presence of the three women does not seem to have led to an impetus, either fashionable or socially conditioned, for the adoption of this distinctive form of embodiment on the island,” they concluded when discussing the rare examples of Viking body modification.

Detail of filed teeth from one of the graves on Gotland. Teeth filing is another example of the bizarre Viking body modification customs that existed during the Viking age. (Lisa Hartzell / Current Swedish Archaeology / CC BY 2.5 SE)

A Unique Viking Initiation Practice

While skull elongation never caught on, the opposite was true of teeth filing among males. The researchers identified 130 cases of teeth with grooves filed into their faces among the skeletal remains of Scandinavian men who lived during the Viking Age. These skeletons were found in many locations, including on Gotland.

Toplak and Kerk propose that the tooth filing represented some type of initiatory rite. Those who underwent the procedure, which undoubtedly caused a degree of prolonged pain, would have been recognized by their peers as belonging to a special or privileged group. But what kind of group? Perhaps one based on trading or commercial interests, the researchers suggested.

“Depending on their concentration on important trading hubs, we postulate that this (or these) social groups might have been closed groups of merchants, similar to later guilds,” Toplak and Kerk told Newsweek. “Their members could identify themselves through their teeth filings and may thus have received commercial advantages, protection or other privileges. This theory also implies that larger, organized communities of merchants existed already in the Viking Age, before the existence of formalized guilds.”

Regardless of the reason for the procedure, it gave those who’d undergone this unusual form of Viking body modification a distinct look that identified them instantly as representatives of the Viking culture.

Why Some Cultural Practices Take Hold, While Others Do Not

All evidence shows that teeth filing in Europe was a Scandinavian Viking innovation. The practice first appeared just a few decades before the official beginning of the Viking Age. It disappeared during the late stage of this distinctive historical period.

Skull elongation, however, clearly came from farther to the south and east, which likely explains why it didn’t become a widespread custom on Gotland or anywhere else in Scandinavia. The three women with the elongated skulls on Gotland undoubtedly got a lot of attention because of their rare condition, but it was not the kind of attention that resulted in others wanting to emulate them. This suggests that elongation was viewed as a foreign import, and thus only appealed to those who had some type of cultural or social connection to the lands of southeastern Europe.