Çatalhöyük: One of the Oldest Recorded Cities in History

The earliest known city, Çatalhöyük gives us an exciting glimpse into the lives of the ancient people who transitioned from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle into city-builders.

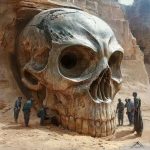

Overlooking the Konya Plain in Southern Anatolia, Turkey, is one of the most fascinating places in all of human history. It is here that human beings in the area abandoned a nomadic lifestyle and began building one of the oldest cities on record. Today, the site is known as Çatalhöyük.

Built on an artificial hill called a tell, Çatalhöyük was inhabited for around 1,400 years. Successive generations rebuilt on top of old buildings, eventually culminating in 18 layers of settlement.

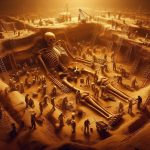

Digging so far into the past is a difficult but wondrous process for the archeologists involved, who, through their work, have helped to bring us the story of the mysterious people who lived there.

Discovery, Excavation, & Scandal

Eighty-seven miles (140 kilometers) from the twin-coned volcano of Mount Hasan and standing 66 feet (20 meters) above the Konya plain is the mound on which Çatalhöyük was built. With a panoramic view of the surrounding area of wide open plains, Çatalhöyük was ideally located.

The site was first excavated in 1958 by English archeologist James Mellaart and his team, who returned in 1961 and worked on the site until 1965. The excavations revealed that the site had 18 layers of inhabitation of advanced culture during the Neolithic and late Neolithic periods. The bottom layer, being the oldest, was dated to around 7100 BCE, while the top layer was dated to about 5600 BCE.

Mellaart was later implicated in the Dorak Affair, in which he published drawings of Bronze Age artifacts from shallow graves in the city of Dorak, near the ancient site of Troy. These artifacts went missing, and Mellaart was accused of smuggling the items from Turkey. Whatever the truth, Mellaart became persona non grata and was only allowed to excavate in 1965 as an assistant. Nevertheless, Mellaart still gets the bulk of the credit for the initial excavation of the site.

It wasn’t until 1993 that excavation at the site resumed. The archeologist in charge, Ian Hodder, was a student of Mellaart and worked on the site until 2018 when his excavations finished. In the first year alone, Hodder and his team unearthed over 20,000 items.

Digital collection methods and radiocarbon dating have contributed greatly to recent excavations and helped archeologists create new pictures of life in Çatalhöyük. New excavations are planned for the future.

The Structures of Çatalhöyük

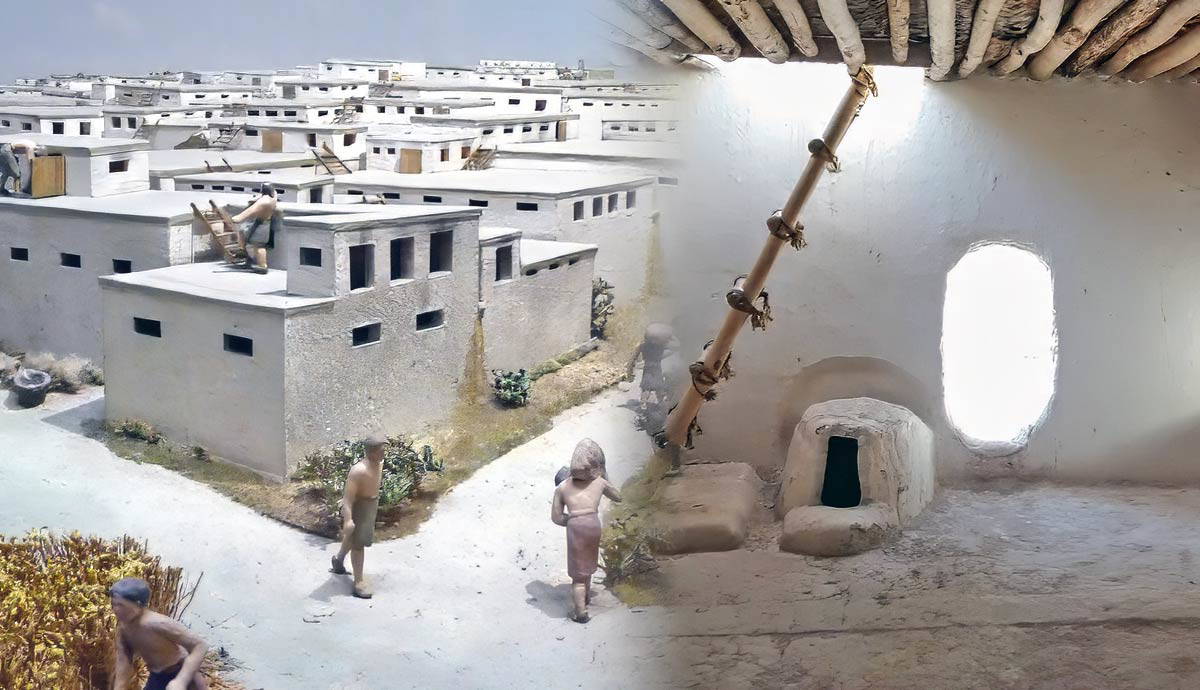

Çatalhöyük was comprised completely of residential mudbrick buildings. There were no warehouses or public buildings. The houses were crammed tightly together, sharing walls, so much so that the city had no streets, and most buildings had no access at ground level. Instead, buildings were accessed via ladders to doors on the roofs. These roof openings also served as the only form of ventilation in many of the houses. Therefore, the city roofs served as the streets.

Virtually every house discovered at Çatalhöyük was found to be decorated with ochre murals of geometric and figurative painting. These designs, in some cases, were refreshed regularly. Many of the paintings also feature wild animals and hunting scenes involving aurochs and stags.

This indicates that although sedentary, the people of Çatalhöyük still practiced hunting as an important part of acquiring food. A common feature found in many homes was bull horns used as decorative and functional items. They were turned into seating in communal areas with the horns pointing forward. Other items from animals, such as teeth and beaks, were used to decorate the walls and often plastered over.

The houses usually had several rooms, including two main rooms connected to ancillary rooms. Raised platforms created a surface on which activities such as cooking could be done. The walls were plastered, and each house had a cooking hearth or an oven.