Double feature: First genetic evidence of a mother-daughter double burial in Roman period Austria

Abstract

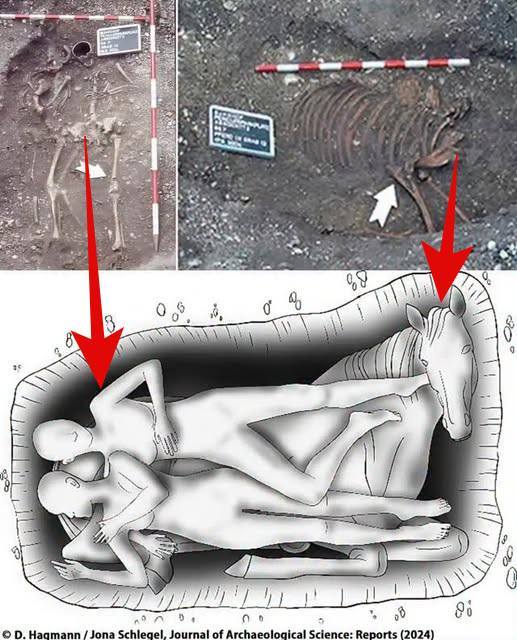

A human double burial combined with a horse interment, discovered in 2004 in the eastern cemetery of the Roman town of Ovilava (today Wels/AUT), has been the subject of a comprehensive interdisciplinary study. This burial was remarkable for two reasons: firstly, the arrangement of the two individuals, with individual 1 having an arm around individual 2, and secondly, the presence of equine skeletal remains in the same burial pit directly below the human remains. Based on this finding, an initial assessment suggested a mixed-sex pair buried together with a horse. The horse burial was interpreted as an indicator of an early medieval date. The position of the two human skeletons suggested that a male and female individual had been buried together. A thorough examination of both the human and horse skeletons disproved these initial interpretations. Radiocarbon dating of the human and horse skeletons dated them to the Roman period. In addition, ancient DNA (aDNA) analysis of the human remains corrected the earlier sex assumption, revealing that the individuals were two biological females who were first-degree relatives. The age difference of 15 to 25 years between the two suggests a probable mother-daughter relationship. Thus, the application of scientific methods confirmed a rare, combined human-horse burial from Roman antiquity and established the first genetically documented mother-daughter burial from this period in present-day Austria.

Graphical abstract

Keywords

Double burial

Horse burial

Mother-daughter burial

Bioarchaeology

Radiocarbon dating

aDNA

Roman archaeology

1. Introduction

The identification of family burials is of particular importance for the reconstruction of social structures and kinship of prehistoric and historic populations (Alterauge et al., 2021, Dzehverovic et al., 2023, Zupanič Pajnič et al., 2023). For a long time, the kinship of buried individuals could only be estimated by morphological similarities of their teeth and skeletal epigenetic traits (Alt and Vach, 1998, Slavec, 2005, Haak et al., 2008). The development of ancient DNA (aDNA) analysis made it, among others, possible to test the genetic relationship of single individuals at a burial site with a high degree of reliability. In general, using aDNA analyses in an archaeological context represents an excellent example of the importance of scientific methods in archaeology. The “third scientific revolution” in archaeology, epitomized by the advent of aDNA analysis, has become pivotal in reconstructing past genetic lineages and migrations despite facing challenges such as preservation biases, contamination risks, and ethical issues surrounding the bioarchaeological study of ancient human remains (Brown, 2023, Dabney et al., 2013, Damgaard et al., 2018, Díaz-Andreu, 2015, Eisenmann et al., 2018, Foster and Sharp, 2002, Goodwin, 2014, Ho et al., 2014, Kristiansen, 2021, Kristiansen, 2022, Kristiansen and Kroonen, 2023, Kroonen and Kristiansen, 2023, Orser, 2014, Otte, 2015, Ubelaker, 2014, Kristiansen et al., 2023). Recently, kinship or family burials from Neolithic times (Juras et al., 2017, Gomes et al., 2020, Furtwängler et al., 2020), Bronze Age (Parson et al., 2018, Žegarac et al., 2021), Medieval (Gamba et al., 2011, Zupanič Pajnič et al., 2023, Dzehverovic et al., 2023) or Early Modern times (Alterauge et al. 2021), have been increasingly confirmed by aDNA. However, there is still a lack of evidence of genetically confirmed Roman period family burials. Up to now, there is evidence of a father–son double burial, identified through aDNA analysis, from Glevum (Gloucester/GB) in Britain (Cotswold Archaeology, forthcoming). Furthermore, Voong et al. (2017) reported a Romano-British family burial identified by HLA-DR genotyping and mitochondrial DNA analysis from Camulodunum (Colchester/GB) dating in the 4th century AD. To our knowledge, there are still no genetically verified family burials from Roman period in the region of present-day Austria. Therefore, we present new results about a double burial from the Roman period eastern cemetery of the Roman town of Ovilava, today Wels in Upper Austria, where we applied archaeological science methods (radiocarbon dating, spatial analysis, aDNA-analysis, anthropological and zooarchaeological approaches) and integrated them with Roman archaeology. We thus adopt a fused qualitative and quantitative approach that might be called processual-plus or neo-processual in light of the post-processual-inspired qualitative advances that have emerged from quantitatively oriented processual archaeology (Davis, 2023, Djindjian, 2021, Hegmon, 2003, Knüsel and Schotsmans, 2022a, Knüsel and Schotsmans, 2022b).

2. Material and methods

2.1. Historical background and site chronology

The Roman town of Ovilava (coordinates: 48.158886,14.020627 [EPSG:4326 WGS 84]) was situated in the northwestern part of Noricum, approximately 20 km south of the Danube. Consequently, it formed part of the limes’ hinterland, whereas the border zone (“ripa”) along the river Danube is now a UNESCO World Heritage site known as “Frontiers of the Roman Empire – The Danube Limes (Western Segment).” Ovilava was an essential economic and administrative hub in Noricum due to its strategic location at the intersection of key Roman routes. It was primarily a civilian center occupied by traders and artisans rather than soldiers or veterans. The town was founded in the latter half of the 1st century AD. It remained inhabited until the late 5th century, with its peak settlement period believed to be mainly in the 2nd century AD (Fig. 1). Shortly after the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD, it is said that the remaining post-Roman population was evacuated to the south in 488 AD by the order of the barbarian king and new ruler of Italy, Odoacer, marking the end of post-Roman settlement, which followed the conclusion of Late Antiquity. The site was reoccupied in the early 7th century, likely by Germanic Bavarians (Breeze et al., 2023, Hagmann et al., 2023, Hausmair, 2022, Miglbauer, 2015).

ns.